The Work Of Education in the Age of E-College & Campus Pipeline by Chris Werry

1. Introduction

Online education has become a topic of much debate within the academy in recent years. Martin Irvine, Associate Vice President for Technology Strategy at Georgetown University states that ‘Internet-based distance learning or elearning is on every educator’s and corporate leader’s agenda’, and that we are at the beginning of an ‘elearning revolution’.[1] There has been a mad rush by universities, venture capitalists and corporations to develop online courses, virtual universities, education portals, and courseware. The drive to develop a winning formula for commercial online education has fostered some unusual partnerships, as ‘Internet entrepreneurs, Nobel laureates, Ivy League schools, textbook publishers, venture capitalists, corporate raiders, and junk-bond kings’ look to education to drive the next wave of Ecommerce.[2] In typically understated terms John Chambers, CEO of Cisco Systems has called online education the ‘second wave’ of Internet commerce, and argued that

The next big killer application for the Internet is going to be education. Education over the Internet is going to be so big it is going to make e-mail usage look like a rounding error.[3]

The number of online classes offered by universities and colleges has grown rapidly. In 1999 one in three U.S. colleges offered some sort of accredited degree online, and approximately one million students took online classes (13 million take traditional classes only)[4].

In this paper I provide a broad overview of some models of online education and the virtual university that have been developed by commercial and academic institutions. I examine some of the rhetorical strategies that have been used to talk about online education by commercial groups, and discuss some of the hopes and fears that have been associated with online instruction by academics, administrators and businesspeople. I outline some of the main players and positions in debates about online education, and I suggest some strategies that we in the academic community might consider exploring.

2. Education Meets Ecommerce, or Michael Milken’s Plot to ‘Eat Our Lunch’

“You guys are in trouble and we are going to eat your lunch†(Former junk-bond king and education entrepreneur Michael Milken, on the future of higher education.)[5]

Private investment in online education went from 11 million in 1993, to just under a billion in 1999[6]. Wall St. analysts, accountancy firms, Internet entrepreneurs, and university administrators routinely tout the commercial potential of online education, and a variety of groups, both academic and corporate, have developed models of commercial online education. According to a report issued in 1999 by Merrill Lynch called “The Book of Knowledge: Investing in the Growing Education and Training Industryâ€, the digitization of education has made the university ripe for the kind of rationalization that took place in the health industry in the 1990’s[7]. The report prompted some Wall Street analysts to predict a future of “EMO’sâ€, or ‘Educational Maintenance Organizations’. Two major investors in for-profit education, former junk bond king Michael Milken, and Paul Allen, co-founder of Microsoft, have gone so far as to make EMO’s their explicit model. The New York Times reports that

“They [Milken and Allen] say they will turn the $700 billion education sector into “the next health care” — that is, transform large portions of a fragmented, cottage industry of independent, nonprofit institutions into a consolidated, professionally managed, money-making set of businesses that include all levels of education.â€[8]

According to Bianchi, traditional universities now find themselves ‘part of a new competitive marketplace with other online learning providers like UNext (part of the Knowledge Universe), KaplanCollege, University of Phoenix Online, Jones International University, and over 400 new companies entering the online learning marketplace.’ And it is predicted that this marketplace will become increasingly global as the digitization of education enables education providers to reach previously local, isolated markets. Woody states that education entrepreneurs in the U.S. are betting that people all over the world “are as hungry for U.S. education as they are for Baywatch.â€

Many universities have responded to the specter of increased competition by launching online courses and virtual universities of their own, by forming coalitions with other universities, or by forming partnerships with corporations (for example UC Berkeley has granted AOL the worldwide rights to market, license, distribute and promote a number of its online courses.) Woody writes that elite universities and professional schools have been scrambling to “leverage their brands”, and to organize their own systems of online education. He states that:

Fearing that they will be left behind, Ivy League administrators are becoming dealmakers, and buzz phrases like “leveraging brands” and “tapping intellectual capital” echo from the Stanford Quad to Harvard Square… Now that this gold mine of intellectual property can be packaged and sold online, universities are determined to share in the profits. “The idea that all of this content – we used to call it teaching and learning – can be turned into content with an economic value is extraordinary,” says Geoffrey Cox, a Stanford University vice provost. “Frankly, if anyone is going to get the economic value of that, it will be the university.”

Over the last three years Ivy League schools have, in fact, developed some of the most aggressive and sophisticated examples of commercial online education, which I will discuss in more detail in the next section.

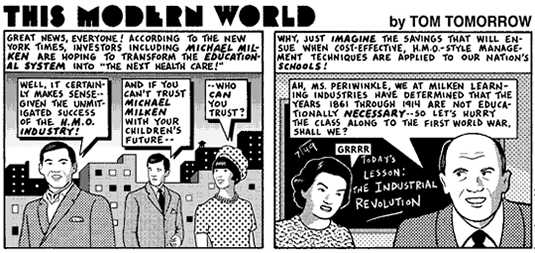

News of some of these developments has not been well received by many academics. A cartoon by Tom Tomorrow sums up many educators’ fears about Milken and Allen’s dream of ‘EMOs’, and of a corporatized higher education:[9]

For some teachers the digitization of education has become connected to a set of issues that the cartoon points to: the corporatization and commercialization of higher education; the casualization of working conditions; loss of control over the product of academic labor, and concern that university administrators are becoming vendor-agents and corporate managers rather than scholar-administrators. Many of these concerns were foregrounded in Fall 1999, when roughly five hundred American universities began outsourcing web, email, courseware and administrative services to ‘education portal’ companies such as Campus Pipeline. In some instances this meant that online courses would be taught via systems produced by outsourcing companies, and email would be sent via the companies’ systems, which were to be advertising-supported. I first became aware of the situation when reading an article in the New York Times called ‘Welcome to College. Now Meet Our Sponsor’. I forwarded the article to the newsgroup H-rhetor, a discussion list for teachers of rhetoric and composition. Several people who were at universities where the outsourcing was going on posted comments about their experiences. Their posts made it clear that they found several aspects of the process troubling:

For some teachers the digitization of education has become connected to a set of issues that the cartoon points to: the corporatization and commercialization of higher education; the casualization of working conditions; loss of control over the product of academic labor, and concern that university administrators are becoming vendor-agents and corporate managers rather than scholar-administrators. Many of these concerns were foregrounded in Fall 1999, when roughly five hundred American universities began outsourcing web, email, courseware and administrative services to ‘education portal’ companies such as Campus Pipeline. In some instances this meant that online courses would be taught via systems produced by outsourcing companies, and email would be sent via the companies’ systems, which were to be advertising-supported. I first became aware of the situation when reading an article in the New York Times called ‘Welcome to College. Now Meet Our Sponsor’. I forwarded the article to the newsgroup H-rhetor, a discussion list for teachers of rhetoric and composition. Several people who were at universities where the outsourcing was going on posted comments about their experiences. Their posts made it clear that they found several aspects of the process troubling:

1) As a faculty member at [deleted] university I can tell you there are two reactions to this article: so what, and WHAT?!!! Most of the “so what” responses come from administrators, who think this is a great way to reduce costs. The “WHAT?!” responses are coming from faculty, who were not consulted about this. Not a big surprise, there.

The commercialization and out-sourcing of campuses has been going on for quite some time, as we’re all aware. But this crosses a line, for me. Now if I send messages out to my class, those messages come through an interface of advertisements or “sponsorships.” I’m not sure what long term impact this will have, but I do know that it bothers me. Dr. [deleted]’s office hours are brought to you today by Amazon.com.

2) When our university began to outsource web-based courses intellectual property was a big issue. In our case, anything placed on the company’s web site belonged to the university. In response, many people did not put anything on the web site that they had developed themselves or planned to use in research or a textbook. Instead, they would send this material to students via e-mail. As teachers, if we don’t own the material that we produce for our courses, what do we own as professionals?

The concerns expressed by these two teachers have been echoed by scholars writing about online education and the virtual university. Tim Luke has written a number of critiques of the trend toward what he calls ‘thin, for-profit, and/or skill competency versions of virtual universities being designed by corporate consultants and some state planners’. David Noble has argued that as teaching materials and knowledge production goes online, the ability of the corporatized university to automate, commodify, reproduce and claim ownership rights over academic work expands. Noble’s account of the strike at York University in 1998 has become an oft repeated cautionary tale in discussions of online education. In ‘Digital Diploma Mills’ Noble describes how teachers at York University in Canada were required to put their research and teaching materials online, and to sign ownership rights to the university (faculty refused, going on strike over this, and eventually won.)

Yet some of the fears associated with online education may perhaps be a little overdrawn. To a significant extent the dreams of corporate planners and educational entrepreneurs remain just that — dreams. As the dot.com bubble burst in the last quarter of 2000, many of the most ambitious for-profit online education companies have either gone bankrupt or radically scaled back their business plans. Online education is still in its first stages, and the term itself perhaps suggests a unity that is belied by the enormous variety of practices that are currently being carried out in its name. In the section that follows, I sketch some broad trends in online education. I then go on to discuss some of the main constituencies involved in debates about online education, how it is talked about, and how the academic community might respond to some of the challenges posed by the digitization of the university.

3. Some Broad Trends within Online Education

3.1 Networks of ‘Informal’ Online Education

Some groups have focused on organizing and commodifying the informal, undisciplined, semi-professional knowledges that circulate within academic communities. This general strategy of making money from the resources and knowledges produced by online groups originated with commercial community developers such as Keen, Infomarkets, and Experts Exchange.[10] These organizations invite community members to assemble resources and pieces of information (technical information, jokes, recipes, stock tips, etc.). Member-generated content is then sold as part of an online information market or auction, used to gather demographic information, or generate advertising revenue. This business model focuses on making money from the valuable and extensive “collective expertise†that ecommerce analysts Hagel and Armstrong argue exists within many online communities. [11]

Some companies have extended this model to the higher education sector. For example InstantKnowledge pays graduate students and teaching assistants to take work they have done (summaries, papers, book reviews, etc.) and make it available to students on the InstantKnowledge.com site. An email message sent to graduate students by the company in February 2000 states:

www.instantknowledge.com – a place to connect, build community, exchange ideas, and earn a professional wage.

IK knowledge producers from around the world earn money–quickly–write about the books they love, edit the best knowledge on the Web, and deliver the news.

Join a growing movement of scholars benefiting from the power of the Internet to break down walls that have separated the sources of knowledge – scholars – from those who need it most – students.

And in July 2000 their web site invited graduate students to ‘earn money doing what you love – creating knowledge, building community, establishing career credentials. Take control of your academic career – offer your knowledge beyond the scope of the university, to the world, through the Internet’. The site organizes and hosts the materials produced by graduate students and TAs, and makes money from sponsorships, advertising and co-branding. InstantKnowledge is one of many commercial online education companies that do not offer courses per se, but do provide a range of services and resources to university students. Other companies provide online tutoring services, test advice, and collect databases of student-centered course, professor and university evaluations (needless to say the criteria constructed are often quite different from the ones used to evaluate our classes). These services function as an informal, largely invisible (to most academics, at least) network of educational materials, advice and knowledges that may, over time, subtly recontextualize aspects of the educational work we carry out.

3.2 EduCommerce

Some elearning companies have organized free online courses as a way of selling and promoting products. A group originally called ‘NotHarvard’ (they recently changed their name to ‘Powered’, after a legal battle with the actual Harvard) is one of the pioneers of this business strategy, which they describe as ‘Educommerce’. Educommerce is defined on their website as:

EduCommerce:

1. The next big thing.

2. Using free online education as a powerful customer acquisition tool – enhancing your customer value proposition.

3. Free online education as a sales and marketing weapon to drive greater stickiness, deeper customer intimacy and higher brand loyalty resulting in incremental revenue.

4. Because sellers need to teach and buyers want to learn.[12]

Classes are free, and are typically organized around products (for example NotHarvard produces photography classes on behalf of vendors of photographic equipment.) Often the classes recoup costs through urging students to buy an accompanying book or piece of software; through advertising, the collection of demographic information, and through marketing and promotion revenues.

3.3 College Portals and the Outsourcing of Computing Services

The online components of education and administration have been outsourced in a number of North American universities. Campus web sites currently constitute an important part of enrolment, applying for aid, running courses, and a host of other administrative and educational activities. These sites, and the services they provide, have been outsourced to companies such as Campus Pipeline and eCollege. In fall 1999 over 500 American universities outsourced web, email, courseware and administrative services[13] (this sector has been described in ecommerce literature as the ‘education portal industry’). Many of these services are advertising supported, funded by advertising and marketing integrated into web and email services (universities can opt to pay more and get the advertising-free version). As Clark describes, the education portal industry constitutes something of a holy grail for many advertisers and marketers. College portals enable advertisers to reach the most mobile, elusive and valuable demographic in America – college students. Clark describes the ‘must-use functionality’ of Campus Pipeline, an outsourcing company that has taken over web and email services at his campus:

What keeps many investors away from other portals such as Yahoo! or Excite is that it takes a lot of effort to build up customer loyalty so that they continue to use only one portal. But with Campus Pipeline, portal loyalty is built-in, since students do not have a choice. Many investors see this as a tremendous economic advantage. Fredric Harmon, the head of Oak General (one of Campus Pipeline’s partners), noted that without this must-use functionality, and forced loyalty, the cost of creating that community of users and replicating that recurring traffic pattern would be enormous.)

It has mostly been cash-strapped universities who have signed on to advertising sponsored college portals, although in some cases schools seeking to cut costs have also signed up. The outsourcing of services has caused some concern over copyright issues, and about the future organization of online resources produced by teachers and researchers. And of course there have been concerns about the commercialization of education that college portals embody. A recent advertisement by Peoplesoft designed to parody advertising-driven portals (PeopleSoft charges a flat fee and does not offer an advertising supported service) captures nicely the concerns that some in the university community feel:

The image shows a campus with lush green lawns, classical architecture and a brick frontispiece displaying a sign that reads ‘State College’.[14] The sign is surrounded by crude advertisements. The caption underneath the image reads: “Will your school’s new Internet portal reflect your image?†The advertisement promotes the “PeopleSoft Portal for Higher Educationâ€, which is described as ‘the first Internet portal that gives you complete control over content. So you’re free to communicate the unique character of your institution – without the clutter of commercial advertisers.’ This image is clearly meant to warn colleges who sign up with rival, advertising-driven services that they risk projecting an image of themselves in cyberspace that is crude and déclassé. It is still too early to tell what impact outsourcing is having, however Blumenstyk notes that the few studies that have been suggest that its success can most charitably be described as ‘mixed’.

3.4 Homegrown Extensions/Adaptations of Existing Classes

By far the most common form of online education consists of teachers extending or adapting traditional classes in a variety of context-sensitive ways. A vast set of teacher-driven experiments have taken place over the last few years as courses are translated to the online sphere, or are supplemented with an online component.

3.5 Online Courses and “Brand-Name†Subsidiaries

A number of non-accredited programs are currently being taught online. The courses offered are oriented toward business and technical subjects, and are offered by subsidiaries of well-known universities (the subsidiary status of the institution can prove useful when it comes to the tax-exempt status of the parent university). Despite the fact that the subsidiary institutions offering the courses can’t grant degrees, the ‘brand name’ of the parent institution is often strong enough to attract students. For example Carnegie Mellon University has formed a subsidiary called Carnegie Technology Education.[15] Carnegie Technology Education develops online courses and infrastructure for businesses and universities in the U.S. and around the world. Similarly, Columbia University has set up a subsidiary called Morningside Ventures Inc. Columbia’s model involves providing free pages that ‘feed into profit generating areas, such as online courses and seminars, and related books and tapes.’[16] The courses provided by these subsidiaries often have faculty producing content or acting as advisors, with TA’s running the classes.

3.6 The Accredited Virtual University

With the arrival of Jones International University, higher education found its ‘first fully accredited online university’[17]. Jones International University was granted accreditation by the U.S. regional accreditation agency in March 1999, and is the first online university to become fully certified by the Global Alliance for Transnational Education. Courses at Jones International are taught over the Internet by part-time, free-lance teachers located in universities all over the U.S. The courses are highly modular and all involve business subjects. There is no regular faculty or participatory governance system, and no research is carried out. Critics of Jones International argue that although it has the term ‘university’ in its title, it ought not be considered one. Altbach argues that Jones International is merely a credentialing service, ‘a degree delivery machine, providing tailored programs that appeal to specific markets.’[18] The American Association of University Professors has fought to prevent accreditation of Jones University, along with similar online programs.

3.7 The Open University’s ‘Mixed Model’

The Open University began in the U.K., and now has branches in the U.S. and around the world. It began by offering correspondence courses, and has become a major provider of distance education classes. The Open University is non-profit, and offers courses in a broad range of disciplines. It draws strategically on a variety of media, and mixes face-to-face interaction with online communication. The courses are aimed at a mixed audience (corporations, university students, the general public).

3.8 Course Aggregators

Course aggregators are academic and business organizations that specialize in taking online courses from a variety of different institutions and assembling them into a single electronic catalogue. The business model often invoked by course aggregators is Amazon.com or Yahoo. Hungry Minds is currently the best-known aggregator of online courses (it was recently purchased by IDG Books, a publishing company whose line includes the “Dummies†series, CliffsNotes and Frommer’s). Their web site states that they offer ‘up to 17,000 courses from top universities like UC-Berkeley, UCLA, NYU, as well as leading training companies and subject experts’.[19] Hungry Minds has signed cross-promotional deals with companies such as AOL and Yahoo in order to get its online courses featured on these portals.

3.9 Online Consortia/Mega-Universities

This describes the strategy whereby groups of related institutions integrate their online courses into a set of programs that are then offered by a single virtual university. This takes three main forms:

A) Consortia of Research Universities

Ivy league schools and top research universities in the U.S. have been quickest off the mark in exploring ways of developing commercial online education. One of the boldest such projects is Unext. Unext is the name of a company that includes a group of top-tier universities (Columbia, Stanford, the University of Chicago, Carnegie Mellon University, and the London School of Economics and Political Science). Unext aims to be the ‘gold standard’ in online MBAs. The Unext web site states:

“UNext.com was created to deliver world-class education. We are building a scalable education business that delivers the power of knowledge around the world. To bring people the finest curricula, we collaborate and co-brand with leading knowledge institutions. Ultimately, we plan to form partnerships with leading establishments throughout the world.†[20]

Unext has created a virtual university called Cardean, via which the group’s online courses are offered (‘Cardean’ comes from the name of a Roman goddess who guarded doorways, and thus alludes to their aim of becoming the major gateway or ‘portal’ to online business education). Two of the largest investors in Unext are Michael Milken, the financier, and Larry Ellison, CEO of Oracle Corporation. Cardean consists of a three-tier system: at the top are the academic “stars†(including several Nobel prize winners) who act on advisory boards and provide ‘insight’. In the middle there are content providers, and at the bottom there are people who process the content and teach students. Cardean is not an accredited university, however it is hoped that the ‘brand name’ of the institutions it draws from will be strong enough to attract students.

B) Regional consortia

Universities within a region have begun integrating their online materials and offering them via virtual universities. For example the Western Governors University is a distance learning consortium created by the governors of 11 western states, as well as Simon Fraser University. Courses are held exclusively online. The web site for the college describes Western Governors University as:

A unique institution that offers degrees and certificates based completely on competencies — your ability to demonstrate your skills and knowledge on a series of assessments — not on required courses. We make it possible for you to accelerate your “time to degree” by providing recognition for your expertise.[21]

Western Governors University has sought accreditation since 1997, however it has so far been unsuccessful.

C) State-wide Consortia

Some community colleges and state university systems have constructed virtual universities for their online courses. For example in 1997 California Virtual University launched a web site that featured ‘the online and distance education offerings of all California accredited colleges and universities.’[22] CVU’s spokesman stated that ‘we’re aiming to be the Amazon.com of the technology mediated education in California’. The virtual university formed partnerships with Sun, Microsoft, Pacific Bell and several other companies. CVU ran into problems when it was revealed that the money donated by these companies was in return for exclusive contracts for the university’s IT and phone services. The project was opposed by teachers and students in the CSU and UC systems, as well as by the American Association of University Professors. In the controversy that ensued, a number of companies left the partnership, and the project has been bedeviled by funding, staffing and training problems. CVU now currently lists over 3400 online courses. However some critics charge that it ‘is little more than a hodgepodge catalogue of previously existing courses with great difference in format and quality’.[23] (their web site seems to confirm this charge). Similar problems have bedeviled attempts by many other universities who have tried to form consortia of this type.

Part 4. Four Positions Taken in Debates about Online Education

There are many positions, constituencies, and players involved in debates about online education. In this section I provide a schematic overview of four of the main positions identifiable: the administrative position, the corporate position, the ‘faculty resistance’ position, and the position of ‘critical engagement’. Obviously the schema below is an oversimplification of the complexity of positions actually being staked out, however it is intended to identify some broad tendencies within the field of debate.

4.1 The Administrative Position

Over the last few years journals aimed at university administrators have tended to focus on how online education can be used to increase student admissions, keep up with technological advancements, and manage costs. For example Irvine compares the costs of traditional education with those of online education, and discusses how ‘expensive overhead’ such as human resources, security and police, counseling and career services, facilities and management, health care and utilities, can be ‘unbundled’ from the educational product with online education. He writes:

The Internet and marketplace demand are the driving forces in unbundling the needed learning experience from the campus-based and high-cost college product. Elearning thus represents a “disruptive innovation,” in Clayton Christensen’s term, because it breaks apart the bundled higher education product into the components desired by a market segment that needs less and at a lower price.

While ‘visionaries’ like Irvine embrace such changes, many administrators are less sanguine about them, and express a degree of anxiety about how to manage the challenges that online education pose. Often they harbor reservations about jumping on the e-learning bandwagon, but worry that if they don’t act fast their university will be left behind – their students and their resources snapped up by corporate/academic competitors, and their star performers cherry-picked.[24] Hayden notes that Michael Crow, the vice provost of Columbia University, has stated that Columbia’s foray into online education was motivated in part by concerns about competition with rival education companies:

Columbia…is anxious not be aced out by some of the other for-profit “knowledge sites,” such as About.com and Hungry Minds. “If they capture this space,” says Crow, “they’ll begin to cherry-pick our best faculty.”

4.2 The Corporate Position

Futurists like Negroponte, corporations such as Microsoft and Cisco Systems, and academic organizations such as Educause (the group that promotes distance education in the U.S.) argue that online education will play a revolutionary role in higher education, that this will lead to the increased corporatization of the university, and that this is generally a good thing. They argue that the digitization of the university will bring about a leaner, flatter, more flexible and efficient institution, one that will more closely resemble the structure of the modern corporation. This argument is often accompanied by claims about the impending collapse of the traditional university. Management guru Peter Drucker famously articulated a version of this position in a Forbes article several years ago:

[T]hirty years from now the big university campuses will be relics. Universities won’t survive. It’s as large a change as when we first got the printed book. Do you realize that the cost of higher education has risen as fast as the cost of health care?… Such totally uncontrollable expenditures, without any visible improvement in either the content or the quality of education, means that the system is rapidly becoming untenable. Higher education is in deep crisis… Already we are beginning to deliver more lectures and classes off campus via satellite or two-way video at a fraction of the cost. The college won’t survive as a residential institution. (Forbes, March 10, 1997)

More recently Mark Taylor, cofounder of the Global Education Network, echoed Drucker’s argument in Educause Review:

“The corporatization of the college and university and the commercialization of higher education will accelerate in coming years. Too many educators live with the illusion that they have a choice about whether or not these changes will occur…whether we like it or not, the restructuring that corporations underwent as they moved from an industrial to a postindustrial or information economy is now occurring in higher education.â€

Such arguments are sometimes expressed with a sense of resignation that is tinged with sadness or nostalgia. However most often the tone is one of revolutionary fervor. The most consistent message is that universities must act now or they will lose out. Irvine writes that if they wait, ‘universities and colleges that could have led the transition of a new business model and could have captured a larger piece of the marketplace for themselves will find that they have become dangerously uncompetitive, like IBM’s mainframe business in the 1980s.’

4.3 The ‘Faculty Resistance’ Position

Some important critiques of online education have been produced by scholars such as David Noble and Cary Nelson. Many of these critiques of online education focus on its potential role in the corporatization of the university, and in the casualization of academic work conditions. Noble warns that online education may lead to ‘digital diploma mills’, electronic sweatshops in which teachers lose control over the products of their labor, and in which their work is automated, reproduced, and commodified. Nelson focuses on how online education may exacerbate academic work conditions in a variety of ways. Noble and Nelson propose strategies of resistance that include demanding faculty control over intellectual property, strengthening tenure, and advancing the struggle for faculty unionization.

Noble and Nelson provide strong critiques of some uses of online education, and they suggest general political strategies that may be useful. However Noble’s arguments in particular entail a withdrawal from the sphere of online education – they do not explore forms of contestation that center on producing alternative models of online education. What is frequently lacking in Noble’s work is an engagement with ways of contesting and reconfiguring online education that are more amenable to the general interests of academics. I would argue that what is needed is a slightly different form of public intellectualism on the part of academics – one that engages sympathetic administrators, and provides them with an alternative to corporate models that have so far dominated discussion. The writers in the ‘critical engagement’ position provide some of the tools to do this.

4.4 The ‘Critical Engagement’ Position

The work of Andrew Feenberg and Tim Luke provides examples of a position I call ‘critical engagement’. Feenberg is a pioneer of online education, while Luke has played an important role in the Virginia Tech Cyberschool, one of the most ambitious and successful programs of online education. Both advocate bottom-up, faculty-driven, craft-style forms of on-line education that carefully adapt existing teaching practices to new technological environments.

Feenberg champions the principles that guided low-tech, text based systems developed in the 80s. He writes:

Could it be that our earliest experiences with computer conferencing were not merely constrained by the primitive equipment then available, but also revealed the essence of electronically mediated education? I believe this to be the case. Even after all these years the exciting online pedagogical experiences still involve human interactions and for the most part these continue to be text based.

But here is the rub: interactive text based applications lack the pizazz of video alternatives and cannot promise automation, nor can they be packaged and sold. On the contrary, they are labor intensive and will probably not cut costs very much. Hence the lack of interest from corporations and administrators, and the gradual eclipse of these technological options by far more expensive ones. But unlike the fancy alternatives, interactive text based systems actually accomplish legitimate pedagogical objectives faculty can recognize and respect.

Feenberg wants to reanimate and extend the educational principles embodied in these earlier experiments. Luke focuses less on issues of technology, and more on the pedagogic, administrative, and political conditions that a successful program of online education should be guided by. He writes that online education must be designed to

change (but not increase) faculty workloads, enhance (but not decrease) student interactions, equalize (and not shortchange) the resources, prestige, and value of all disciplines, balance (and not over emphasize) the transmittal of certain vital skills, concentrate (and not scatter) the investment of institutional resources, and strengthen (and not reduce) the value of all academic services. Technologies do not have one or two good and bad promises locked within them, awaiting their right use or wrong misuse. They have multiple potentials that are structured by the existing social relations guiding their control and application. We can construct the cyberschool’s virtual spaces and classrooms so that they help actualize a truly valuable (and innovative) new type of higher education (Luke, page 156).

The goals elaborated by Feenberg and Luke, and the practical example set by initiatives such as the Virginia Tech Cyberschool may help academics construct alternative models of online education, models that are both pedagogically effective and in line with the interests of the academic community.

Part 5. The Rhetoric of Commercial Online Education

I believe that rhetoricians, along with scholars in many other disciplines, ought to initiate a careful analysis of the rhetoric of online education. It is important that we examine how teachers, students, knowledge, academic resources and community are represented; how key terms are defined and struggled over by different groups, and how persuasive language is used to convince various constituencies of the benefits of particular visions of online education and of the university. In the section that follows I identify several areas where a study of the rhetoric of online education might focus.

5.1 How Online Entrepreneurs Address Different Audiences

One area I have been investigating involves the ways in which commercial developers of online education talk to different audiences, how they tailor their message when talking to teachers, students, administrators and investors. What I’ve found is that when organizations such as Campus Pipeline produce written materials intended for their investors, they stress how the portal locks in the most valuable yet difficult to reach demographic in the country – college students. They stress its ‘must use functionality’ – how it is integrated into different aspects of student life, such as registering for classes, emailing professors, and accessing course information. They focus on the relationships they are forging between students, advertisers, marketers and vendors, and on how they plan to become portals with the kind of influence possessed by AOL or Yahoo.[25]

In materials written for administrators, what is typically stressed is the savings that will be made, and the increases in efficiency and flexibility. The information packets sent to administrators by companies such as Real Education, Jenzabar, and Campus Pipeline often talk of education in terms of a ‘conduit’ model that stresses the efficient transport of educational units (even Campus Pipeline’s name suggests a conduit, and of education conceived in terms of delivery.)

However when courseware vendors or education portals discuss online education in materials intended for faculty, a very different tone is registered, one in which “community†tends to be a central motif. For example issues of The Chronicle of Higher Education are crammed to the brim with advertising from online education companies. A common theme in these advertisements is the notion that the vendor’s software system will enhance ‘community life’ in universities, make academic community resources easier to use, and connect academics with the wider communities outside their gates. Thus Campus Pipeline’s advertising slogan is: ‘a community dedicated to meeting individual needs. A business streamlined for maximum efficiency. And a campus that never closes.’[26] And Campus Pipeline announces in its mission statement: “We will revolutionize education by connecting the collegiate community, enhancing the way higher education builds relationships with its students, faculty, staff and alumni.†In much of the material Campus Pipeline has produced for teachers, the term “community†appears to function as a way of reassuring educators that courseware vendors are sensitive to the social and communicative aspects of teaching. ‘Community’ becomes a way of managing some of the tensions inherent in systems that tend to reify educational practices. The discourse of community appears strategically drawn on to reassure educators – to quiet their fear of automation and of being displaced, and to show that the company understands that education entails issues of culture, communication and socialization.[27]

5.2 The Use of ‘Learner-Centered’, Constructivist Models of Education.

Many proponents of commercial online education stress the need to move from a traditional Fordist, mass production based model of education, to a more flexible, Post-Fordist, ‘mass customization’ model. This is sometimes allied with the language of constructivist, learner-centered approaches to learning – language that talks about the importance of student-centered approaches in which knowledge is constructed within a community of learners. For example Irvine talks of how universities are moving from ‘an academic model with a legacy system tied to industrial and agrarian economies to a learner-centered Internet economy model.’ In some instances the connection between flexibility, mass customization, and constructivist pedagogy is thought through in a principled, sophisticated way. However sometimes this focus on ‘student-centered’ education seems to be used merely as a way of camouflaging shortcomings in models of online education. With some all-Internet courses there is no face-to-face interaction, and there is significant dissociation between different levels of the educational enterprise – between managers, advisors, system designers, content providers, technical assistants, teachers, etc. Furthermore the system is designed to be modular and scalable, so that teaching assistants and adjuncts can be slotted into different courses as required (Irvine proposes that future models of online education will center on ‘reusable learning objects in customized modules with assessments for specific outcomes’.) In such contexts students must, of necessity, show a great deal of initiative. They are at the ‘center’ of the system in the sense that they must take charge of their education in a way that traditional students aren’t required to. However it isn’t clear that this necessarily empowers students, provides for a better educational experience, or is really in line with constructivist pedagogy (there is a sense in which automated phone mail systems in which information is distributed within a network of options could be called ‘learner-centered’; however it is debatable whether this is inherently superior to the traditional ‘instructor-centered’ experience of getting information from a human being).[28]

This impoverished notion of ‘student-centered’ education is often part of an argument that the technology will somehow democratize education and make student-centered learning happen by itself. Thus Andrew Rosenfield, chairman and CEO of UNext.com has stated: “lectures are dead. They are not a good way to learn…People want to learn what they need to know, not what professors want them to know. You can only do that on the Internetâ€.[29] The technological-determinist argument that the Internet has the miraculous ability to democratize and empower its users is familiar enough. However Rosenfield appears to extend this argument to say that the Internet will also democratize education and empower students. Rosenfield often invokes student-centered, constructivist goals, and yet the courses offered so far by Unext appear to approach such goals in a rather superficial way.

5.3 E-commerce and Online Education.

Many concepts, themes and categories derived from electronic commerce have been influential in discussions of online education. This is hardly surprising given that many companies involved in electronic commerce (and in particular companies involved in commercial online community development) have moved into the area of online education. I will discuss some of the most commonly used ones.

‘Disintermediation’

‘Disintermediation’ is often talked about in relation to online learning. It is proposed that the digitization of education will enable teachers and students to interact in ways that are less encumbered by the traditional bureaucratic structures of the university. This is an interesting claim, given how the new technological interfaces involved seem hardly to reduce the need for ‘mediation’. And when one looks closely at enterprises like Unext or Jones International, instead of disintermediation, one finds complex forms of ‘remediation’. In fact many new layers of mediation appear to be involved, since in order to make teaching as modular, scalable and automated as possible, traditional faculty roles get differentiated and parceled out to networks of advisors, content providers, teachers, technicians and administrators. A number of E-commerce texts have argued that claims about the Internet’s role in disaggregation and disintermediation are greatly exaggerated. Downes and Mui write that ‘in many sectors intermediaries have proven to be remarkably robust. Long chains are being taken apart, but they are also being put back together in new configurations.’ (Downes and Mui, page 152). Ester Dyson, the head of ICANN, has argued that claims about the disintermediation brought about by the Internet are often misguided. She writes:

Contrary to the notion that the Net will be a disintermediated world, much of the payment that ostensibly goes for content will go to the middlemen and trusted intermediaries who add value—everything from guarantees of authenticity to software support, selection, filtering, interpretation, and analysis.[30]

So it would seem quite likely that some of the models of online education we have looked at will not involve disintermediation so much as they will involve different kinds of mediation, by different groups of people, perhaps residing to a greater extent outside the university.[31]

‘Internet Democratization’

Electronic commerce texts often talk about the democratizing effects of the Internet. Discussions of online education often make corresponding arguments. Mccright describes a talk given by John Chambers, CEO of Cisco Systems, in which the democratizing potential of online education is stressed:

Through e-learning, he [Chambers] said, employees will be able to take more control of -their jobs, while the dispossessed of the world will be able to make strides to improve their economic position.

Irvine makes a similar argument. He writes that the emerging system of online education, which he calls the ‘Internet Elearning Model’, produces a ‘shift in authority and agency to the learner’. He writes that the ‘demand driven economy of the Internet, which communicates the needs of customers and suppliers more rapidly than ever before’, is paralleled by the ‘learner-centered paradigm of elearning, in which the learner-customer has far more authority, control, choice, and agency in personal learning and knowledge production.’ Yet the notions of democracy and agency advanced in such arguments are often very limited, and are closely tied to consumption model of education. Furthermore, the argument that the digitization of education will democratize learning is often at odds with the idea that in order to move quickly in the Internet-age, deliberative democracy within the university itself must be lessened. For example Taylor writes:

The defining characteristic of network culture is speed; only the quick survive. The current organization and decision making structure of colleges and universities cannot respond quickly enough…In many cases deliberative processes will have to be streamlined and decision-making responsibility delegated to individuals with the necessary expertise. Taylor, page 45.

It would thus seem that increased ‘consumer/student choice’ and flexibility must come at the cost of a decrease in deliberative democracy for teachers and researchers.

‘Frictionless Education’

There is much talk of the new, more ‘frictionless’ education market, where students anywhere are able to engage in classes that suit them. It is often claimed that the digitization of education will one day enable everyone on the planet to take classes by Harvard professors. And while increased accessibility is certainly a possibility, the trouble with this way of thinking about education is that it reduces education to delivery, and underestimates how other aspects of E-commerce models run counter to this. A number of Ivy League schools have in fact made it clear that they are pursuing a policy of price differentiation, and so won’t mass market their courses precisely because they don’t want to damage their ‘brand’. The dean at Duke’s Fuqua online business school, which offers a virtual MBA writes: “We could offer 60,000, 100,000 MBAs, but we want to be an incredibly desired product that far more people want than can get†(an online MBA from Duke currently costs $90,000). The way around this problem, according to Irvine, is to ‘segment the total market served and bring differentiated products to the marketplace of learners’. However this seems to run somewhat counter to the ‘frictionless’ ideal in which the highest quality education can be reproduced and made available to anyone anywhere.

‘Disaggregation’, or the Unbundling of the Educational Experience

Educational Entrepeneurs often argue that just as the Internet has fostered decentralization and disaggregation in a variety of traditional markets, a similar process will take place in the education market. Irvine writes that:

The Internet is allowing entrepreneurial companies and innovative colleges to unbundle learning and credentialing services from the whole campus-based industry with its high cost of research and residential services and to deliver these services to a growing marketplace. The elearning revolution has only just begun to capture the promise of the democratization of knowledge made possible with Internet technologies.

Irvine proposes that the ‘core’ services and products provided by the university will be disaggregated from the peripheral ones; a variety of differentiated services and products will emerge in order to cater to different market segments, and that this process of unbundling will enable highly flexible forms of mass customization. The viability of this paradigm is dependent on the extent to which education can be divided up into modular, scalable units, which remains an open question.

6. Solutions?

There is an urgent need for critical work by academics that deals with the complex specifics of discourses, technologies, institutions and economics shaping online education. Too much academic work ignores the most important forces shaping online education, leaves large areas of debate uncontested and doesn’t really speak to groups actively involved in new media who could constitute potential allies. When it comes to how we might think about the future of online education, there are several areas that I think academics need to focus on.

1. Give Administrators Alternatives

As I argued above, I believe that academics need to do more to engage sympathetic administrators and provide them with constructive alternatives. Feenberg tells an interesting story of the time he met the Chancellor of the California State University system and discussed CETI, an ambitious online education project that involved the construction of a significant amount of new technological infrastructure. Feenberg asked the Chancellor what pedagogical model had guided CETI. Feenberg writes that: “the Chancellor looked at me as though I’d laid an egg, and said, ‘We’ve got the engineering plan. It’s up to you faculty to figure out what to do with it’. And off he went: subject closed!†Feenberg is surprised by this response, and states:

Would you build a house this way or design a new kind of car or refrigerator? Surely it is important to find out how the thing is going to be used before committing a lot of resources to a specific plan or design. Yet this was not at all the order in which our Chancellor understood the process. Why not? I would guess it is because he did not conceive of the technology of online education as a system, including novel pedagogical challenges, but as an infrastructure, an “information superhighway,” down which we faculty were invited to drive. And just as drivers are not consulted about how to build the roads, so faculty were not much involved in designing the educational superhighway.

Feenberg’s concern is justified, and one might expect that teachers would generally take a more enlightened view. However it is by no means clear to me that the Chancellor’s assumptions are greatly different from those held by many teachers. For example, the American Association of University Professors, a key policy making organization within academia, recently came up with a policy paper on distance and online education. The document produced by the AAUP outlined the rights and responsibilities of faculty. Here is an excerpt:

The institution is responsible for the technological delivery of the course. Faculty members who teach through distance education technologies are responsible for making certain that they have sufficient technical skills to present their subject matter and related material effectively, and, when necessary, should have access to and consult with technical support personnel. The teacher, nevertheless, has the final responsibility for the content and presentation of the course.[32]

What is striking is the way the document reproduces some of the assumptions that Feenberg ascribes to the Chancellor. The language of the document recreates a split between pedagogy and technology, between providers and users. It still thinks of technology primarily as a delivery mechanism for teaching, rather than a new environment. And it does not make the case that academics ought to have a significant role in shaping that environment.[33] I believe that we ought to play a role in shaping that environment, and that we need to provide constructive alternatives for administrators in order to make this happen. If resistance to ‘thin, for profit’ models of online education proceeds via claims that education and academics are somehow ‘special’, exempt from conditions that so many others must work under, then we run the risk of being represented as backward, obstructionist and selfish. We need to offer alternatives as well as critique, and we need to link our struggle to those of other groups.

2. Ensure Control of Academic Resources & Construct Strategic Alliances

It is important that academics carefully consider strategies for organizing their resources online. We should explore models that are open, participatory and democratic, that respond to a variety of social interests, include a strong public service commitment, and which embody the kind of broad intellectual mission that characterizes institutions such as San Diego State. I believe that teachers need something like an ‘open source’ movement for on-line academic resources, and that taking a leaf out of the book of groups like the Free Software Foundation, we ought to create something like a ‘Free Courseware Foundation’, which gives teachers greater control of their resources, and better enables them to share materials with other teachers and with the public.[34] Michael Jensen, director of publishing technologies at the National Academy Press, puts the issue in the following terms:

The technical choices we make over the next three years, as individuals and as institutions, will have repercussions for decades. We need to decide what kind of relationship academe should have with the tools that underpin its knowledge bases — that of a huge corporate customer that goes to private industry for software, or of a supporter and underwriter of open and free software tools that serve our needs.

A major obstacle in developing an open source movement for on-line academic resources has not been a lack of expertise or resources or skilled people – it has largely been a problem of organization, coordination, political will, and funding.

In some respects academia as a whole is facing a situation similar to the one that faced by Rhetoric and Writing scholars in the late 1980s and early 1990s (albeit much increased in scale). At this time many writers in Rhetoric and Composition argued that the community urgently needed to produce writing software that was driven by a more sophisticated understanding of writing and electronic literacy than was evident in commercial writing software. Texts such as Paul LeBlanc’s Writing Teachers, Writing Software: Creating Our Place in the Electronic Age made powerful arguments for the importance of software shaped by the insights of writing teachers. Jay Bolter and a handful of other scholars in Rhetoric and Composition built some ambitious software packages for advancing such a project. However the movement was largely unsuccessful, and as a result our students compose with software packages designed not by writing experts, but by Microsoft. I would argue that this failure was in part because each individual foray in developing writing software remained too isolated, and because the developers were not generally committed to an open source model.

If we are to have more success in ventures designed to advance an open source movement for on-line academic resources, we will need to construct much broader sets of alliances. At present a number of organizations are working on projects that are broadly compatible with an open source movement. For example The National Academy Press has begun developing a range of tools that will be made open source when they are finalized. The International Consortium for the Advancement of Academic Publication has developed resources and tools that are open source. The ‘Linguist’ site, which enables communication, coordinates activities, and acts as a repository for the large amounts of electronic text produced by members of the American linguistic community, constitutes an interesting model for the organization of scholarly resources. And the English server, a cooperatively run academic site that publishes humanities texts, journals, and other scholarly collections, has developed a number of tools for managing academic resources.[35] However these remain largely isolated projects. What is needed is coordination, along with institutional and financial support. And we may need to look for allies outside the university. We need to talk to groups involved in the Open Source and Free Software Foundation. Many of these people are sympathetic to the kind of project I’ve described. For example I recently co-edited a book about online community and online education. We invited Richard Stallman, founder of the Free Software Foundation, to contribute a chapter in the book. Stallman was very interested in the issues that the book addressed, and outlined a number of ways in which academics might draw on some of the principles of the Free Software Foundation.[36]

Lastly, we need to ensure that the universities we teach at, and the professional organizations that represent us, produce policy that ensures faculty control of online resources. And when we negotiate contracts with publishers we need creative policies to deal with the issue of future electronic property rights.

3. Examine the Rhetoric of Online Education

We need to critically examine the rhetoric of online education, to analyze the figures, narratives and rhetorical strategies used to talk about it. And we need to produce a history of how it has been talked about. David Noble’s work on the history of correspondence schools is exemplary in this regard. Noble demonstrates that when correspondence courses first emerged, predictions made about its revolutionary, democratizing, transformative effects bear an uncanny resemblance to claims made today about online education.

Part of this project of rhetorical analysis could include constructing a set of criteria for talking about online education. The trends and strategies described in the sections above illustrate the enormous range of uses of online education, and the enormous range of models being experimented with. However within this range there are some broad criteria we can use to start thinking about online education. These include the extent to which control over the construction, organization and delivery of online courses is ‘top down’ or ‘bottom up’; the degree to which the course materials are ‘mixed’ or ‘all-internet’, consist of ‘education in a box’ versus a more holistic approach to education. Many commercial models of online education are designed to be modular, scalable, reproducible, amenable to automation, consistent with the goals of cost-cutting, and with a ‘work for hire’ concept of intellectual property (teachers are hired to produce work that then becomes the property of the hiring agency). Alternative models of online education tend more often to involve adapting new technologies to particular learning communities and sets of pedagogic goals, to constitute an extension of existing practices, and to involve faculty/public ownership. There are of course a range of other possibilities, and many other criteria we can draw on to evaluate online education, most notable those articulated by writers such as Tim Luke and Andrew Feenberg.

4. Proceed Cautiously

Until recently it has been difficult to make the argument that the development of online education ought to proceed slowly and carefully. The argument that academic institutions must ‘lead or bleed’ has been dominant. It may be easier to advocate a more gradualist approach now that the economic situation has changed so much. I believe that Downes provides useful advice when he states:

The way to proceed in online learning is – ironically, given the nature of the Internet – slowly and cautiously. The introduction of new technology must be, as David Jones says, a product of evolution. Pilot delivery and evaluation should be conducted before the announcements and promises are made. Staff should be acclimatized and trained in new technologies and methodologies.

5. Train Students to be ‘Community Architects’

In the E-commerce text Net Gain: Expanding Markets Through Virtual Communities,

Hagel and Armstrong describe how to organize and exploit the resources produced by online communities. They discuss how to train “community architects†whose job it is to “acquire members, stimulate usage, and extract value from the community.â€[37] I would like to suggest that in our teaching practices we could attempt to produce oppositional ‘community architects’. This would entail resituating courses that deal with online information as part of an expanded project of critical practice in which students are seen not just as technical problem solvers, but also as critics who actively intervene in situations in which issues of value, power, and social organization are negotiated. Such classes might promote the idea that it is important that those who are engaged in the design and publication of electronic texts, interfaces, databases, and tools for the formation of online resources think about the cultural, political and social implications of their work. Training community architects could involve looking at how competing discourses and competing information architectures represent the possibilities for organizing online space, activity, access, assembly, public use, control and ownership.

FOOTNOTES

[1] Martin Irvine, ‘Net Knowledge: The Coming Revolution in Higher Education’. Gnovis, volume 1, issue 1, 2001. http://gnovis.georgetown.edu/business/irvine_1.html

[2] “E is for E-school: Dot-com start-ups go to the head of the class.†Alessandra Bianchi. Inc. magazine. July 01, 2000

[3] Chambers, ‘Next, It’s E-ducation’.

[4] These figures are cited in ‘A Virtual Revolution in Teaching’, P J Huffstutter and Robin Fields. Los Angeles Times, March 3, 2000. And “E is for E-school: Dot-com start-ups go to the head of the class.†Alessandra Bianchi. Inc. magazine. July 01, 2000

[5] Cited in Edward Wyatt, “Investors See Room for Profit In the Demand for Educationâ€. New York Times, November 4, 1999, Section A, Page 1.

[6] Eduventure.com’s “The Education Quarterly Investment Reportâ€, February 2000.

[7] The Merill Lynch report observes that while the education and training market accounts for 10 percent of the United States economy, it accounts for less than two-tenths of 1 percent of the value of the domestic stock market — $16 billion out of $10 trillion. Health care, by comparison, represents 14 percent of G.D.P. and a similar percentage of the value of the stock market. The report concludes that there is much room for growth, and great potential for companies to find profits in the education sector.

[8] ‘Investors See Room for Profit In the Demand for Education’ The New York Times November 4, 1999.

[9] The full strip is available at: http://www.salon.com/comics/tomo/1999/11/15/tomo/index.html

[10] See http://www.keen.com, http://www.infomarkets.com, http://www.experts-exchange.com/info/about.htm. I explore this strategy, and the way community has been used in models of electronic commerce in some detail in Werry 2000.

[11] For a discussion of Hagel and Armstrong’s book Net Gain: Expanding Markets Through Virtual Community, and the exploitation of community generated resources in models of electronic commerce, see Werry 2000.

[12] From the NotHarvard homepage in July 2000, http://www.notharvard.com. The site is now at http://www.powered.com.

[13] See Guernsey, “Welcome to College. Now Meet Our Sponsor.”

[14] This advertisement appeared in The Chronicle of Higher Education, July 28, 2000. Page A7.

[15] http://www.carnegietech.org/main.html

[16] See Hayden 2000, “New Profits for Professorsâ€.

[17] This is the slogan on their web site, which is at http://www.jonesinternational.edu.

[18] Philip G. Altbach ‘The Crisis in Multinational Higher Education’ International Higher Education, Fall 2000. http://www.bc.edu/bc_org/avp/soe/cihe/newsletter/News21/text2.html

[19] http://www.hungryminds.com/

[20] Unext is online at http://www.unext.com. Cardean university is at http://www.cardean.edu/

[21] http://www.wgu.edu/wgu/index.html

[22] http://www.california.edu/

[23] Berg, ‘Public Policy on Distance Learning in Higher Education: California State and Western Governors Association Initiatives’

[24] A recent edition of the journal Business Officer showcased many of these concerns. The journal’s theme was “Lead or Bleed: Colleges, Universities and the E-Universeâ€.

[25] Clark provides a useful discussion of these issues in ‘Education, Communication, and Consumption: Piping in the Academic Community’.

[26] This advertisement is taken from the Chronicle of Higher Education, September 03, 1999, page A53. The advertisement appeared frequently between 1998 and 2000.

[27] For a discussion of the contrast between claims made about community in PR material, and the actual design of Campus Pipeline’s web and mail systems, see Clark.

[28] Similarly, the focus on ‘communities of learners’ in some of these models seems to spring in large part from the need to address a consistent problem in distance education – the very high drop out rate. Brian Mueller from the University of Phoenix notes that creating a ‘highly social online experience’ is the key to managing problems with student retention (McGinn, page 59).

[29] Cited in Huffstutter and Fields.

[30] Cited in Addison, 178.

[31] There is perhaps a different sense in which ‘disintermediation’ may occur. Luke notes that one of the problems faced by teachers at the Virginia Tech Cybershool was ‘burnout’, caused in large part by their having to take on a much greater range of technological and administrative burdens. The emergence of the ‘teacher-administrator-technician’ may constitute a kind of disintermediation, however it does not seem like a very favorable one.

[32] Cited in Addison, page 175. The American Association of University Professors “Statement on Distance Education,†is online at http://www.aaup.org/spcdistn.htm.

[33] Addison provides an analysis of the AAUP which makes this case in some detail.

[34] See Stallman, 2001.

[35] http://linguistlist.org/, http://eserver.org/

[36] See Stallman, 2001.

[37] I discuss Hagel and Armstrong’s text in Werry 2001.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Addison, Joanna. ‘Outsourcing Education, Managing Knowledge, and Strengthening Academic Communities’. In Werry & Mowbray, Online Communities: Commerce Community Action, and the Virtual University. Prentice Hall, 2001.

Barker, Michael. ‘E-Education is the New New thing’. First Quarter, issue 18, 2000.

Berg, Gary. ‘Public Policy on Distance Learning in Higher Education:

California State and Western Governors Association Initiatives’. Education Policy Analysis. Volume 6, Number 11, 1998. http://olam.ed.asu.edu/epaa/v6n11.html

Blumenstyk, Goldie. “Colleges Get Free Web Pages, but With a Catch: Advertising”

The Chronicle of Higher Education, September 3, 1999, page A45.

Blumenstyk, Goldie. “Technology ‘Outsourcing’: the Results Are Mixed”. The Chronicle of Higher Education, October 29 1999, A59.

Chambers, John. ‘Next, It’s E-ducation’. The op-ed column, New York Times, November 17, 1999.

Clark, Norman. “Education, Communication, and Consumption: Piping in the Academic Communityâ€. In Werry & Mowbray.

Downes, Larry, and Chunka Mui, Unleashing The Killer App: Digital Strategies for market Dominance. Harvard Business School Press, 1998

Downes, Stephen. ‘What Happened at California Virtual University?’ http://www.atl.ualberta.ca/downes/threads/column041499.htm

Feemster, Ron, “Selling eyeballs,†University Business, September 1999. Online: http://www.universitybusiness.com/9909/eyeball.html

Feenberg, Andrew. ‘Distance Learning: Promise or Threat?’ Crosstalk, Winter,1999. Also available at http://www-rohan.sdsu.edu/faculty/feenberg/TELE3.HTM

Guernsey, Lisa. “Welcome to College. Now Meet Our Sponsor.” NYT, August 17, 1999

Hayden, Thomas. “New Profits for Professorsâ€. Newsweek, February 28, 2000, page 52.

Huffstutter, P J, and Robin Fields. ‘A Virtual Revolution in Teaching’, Los Angeles Times, March 3, 2000

Luke, Tim. ‘Building a Virtual University: Working Realities from the Virginia Tech Cyberschool’. In Werry & Mowbray.

Mccright, John S. “Comdex ’99: Chambers – Education is next e-commerce†PC Week Wed, 17 Nov 1999. http://www.zdnet.co.uk/news/1999/45/ns-11538.html

McGinn, Daniel. ‘College Online’. Newsweek, April 24, 2000.

Noble, David, “Digital Diploma Mills: The Automation of Higher Education,†First Monday, vol.3, no.1, 1998.: http://www.firstmonday.org/issues/issue3_1/noble/index.html.

Stallman, Richard. ‘The Free Universal Encyclopedia and Learning Resource’. In Werry & Mowbray.

Taylor, Mark C. ‘Useful Devils’. Educause Review, July/August 2000.

Werry, Christopher. ‘Imagined Electronic Community: Representations of Online Community in Business Texts’. In Werry & Mowbray.

Werry, Christopher, and Mowbray, Miranda. Online Communities: Commerce Community Action, and the Virtual University. Prentice Hall, 2001.

Woody, Todd. ‘Ivy Online’. The Standard, October 22, 1999. http://www.thestandard.com/articles/display/0,1449,7122,00.html