Argument: An Alternative Model by Said Shiyab, University of Southern Indiana

Introduction

During the last five decades, rhetoricians have been deeply divided over whether rhetoric can be effectively used in teaching composition. Some have argued that rhetoric involves some or all forms of persuasion (Jordan 4). Others believe that it is the arguer’s manipulation of the audience (Herrick 3). These two views, among others, point to the fact that they are, in principle, incompatible to the extent where rhetoricians will never meet. Because of these different views, rhetoricians are in a state of flux as to what strategies or principles should be used when teaching rhetoric and composition.

Despite the lack of consistency, and within the literature of composition, there is clear evidence that some rhetoricians are fascinated by the Rogerian principles as an alternative argument, simply because such principles offer dialogue, cooperation and mutual understanding (Bator 431; Hairston 374). Unlike the traditional argument, the Rogerian principles tend to be non-evaluative, non-threatening, and more soothing. One of the main objectives of this paper is to show how the Rogerian principles can be used as an alternative model to the traditional form of argument, i.e. Toulmin model. An attempt will be made to examine the principles upon which the Rogerian argument is based. Emphasis will be placed on the philosophical and pedagogical dimensions of the Rogerian argument, as these principles seem to be more appropriate and effectively more functional in both verbal communication and written discourse. Above all, the Rogerian principles offer a new look and perspective into the process of argumentation.Â

What is an Argument?

Arguments are built around debatable issues (Rottenberg 3). There are two forms of argument: the pro argument and the con argument. The pro-argument emphasizes a particular point; it argues a point. One might write an argument illustrating and explaining the meaning of some concept or another. Here, there is no need for arguers to take a stance, adopting one side of a debatable issue, but they still need to defend their position with all the persuasive means available to them. The con argument is an argument that adopts a particular perspective on a subject. Arguers take a stance on one side of a debatable and controversial issue. They might argue about gun control: should we impose limitations on owning guns? They might write about the death penalty: should it be allowed?

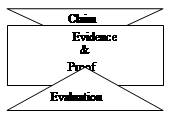

Furthermore, an argument has a controlling idea, a thesis statement. Once the thesis statement is presented, arguers have to explore enough evidence to support their thesis. They also need to make their argument very clear and more effective (Wood 6). Here is a representation of the general argument:

With regard to argumentative strategies, arguments generally start with a good question: Should Capital Punishment Be Controlled? Can Marijuana Be Legalized? Should Euthanasia Be Allowed? All these questions constitute good arguments.  Here, arguers’ debates come from their discontent and discomfort about something they have heard or seen in a specific text. Although arguers might have a good explanation for their debate on a specific issue, they also would like to focus on other perspectives so that they explore the issue further. Such explanation and interpretation of a particular issue becomes part of their argument.

Models of Argument

Models of argument range from the traditional form of argument, represented by the Toulmin model, to the Rogerian model, represented by Carl Roger. The Toulmin model emphasizes that arguers make their claim, support it with evidence and proof, and conclude it with implications or applications without acknowledging the opponent’s argument. The traditional form of argument focuses on producing a description of the real process of argument (wood 140). Its model is based on three principal elements: claim (what the arguer is trying to prove), evidence (proof or grounds for belief), and warrant (establishing the connection between claim and evidence).

As for the Rogerian argument, it can be simply defined as an argument that sympathizes with the opponent’s view. Arguers identify themselves with others’ situations.  They empathize with opposing perspectives in the process of promoting their own positions. Compare the following two situations:

Situation one:Student A: “Fathers are more important than mothersâ€.

Student B:  “Mothers are more important than fathersâ€.

Situation two:

Student A: “Fathers are more important than mothersâ€.

Student B: “ While I understand why some people believe that fathers

are more important than mothers, personally I believe

mothers are more important than fathers.

Rogerian Argument as Alternative

The Rogerian argument is an argument that is ascribed to Carl Rogers who was not a teacher but a psychotherapist (Bator 427).  Rogers believes that when people communicate with one another, their first attempt should focus on reducing tension rather than being confrontational.  Rogers used this strategy as a middle ground between two disputant participants. Here, both writer and reader emphasize what is common between them and not what divides them. Such strategy assumes that both writer and reader can find common ground and, in turn, find a solution to the problem (Wood 303).

This goes along with the Rogerian rhetoric.  Rogers suggests that writers need to eliminate the threat and participate in the argument as partners not opponents. Unlike the traditional form of argument, represented by Toulmin’s model as well as the Aristotelian argument, the Rogerian argument attempt to solve a problem rather than escalating it by attacking a person or an organization.  Rogers states:

I would like to propose, as an hypothesis for consideration, that the major barrier to mutual interpersonal communication is our very natural tendency to judge, to evaluate, to approve or disapprove, the statement of the person, or the other group. Let me illustrate my meaning with very simple examples. As you leave the meeting tonight, one of the statements you are likely to hear is “I didn’t like that man’s talkâ€. Now what do you respond? Almost invariably your reply will be either approval or disapproval of the attitude expressed. Either you respond, “ I didn’t either. I thought it was terrible,†or else you tend to reply, “Oh, I thought it was really good.â€Â In other words, your primary reaction is to evaluate it from your point of view, your own frame of reference. (330)

The above quote bring us to the question of how to keep the audience from becoming defensive and disturbed. Of course, there are different points of view and the audience may sometimes be or feel intimidated by them. In cases such as these, communication fails between arguers and their audience. To foster communication and dialogue, the Rogerian principles can be used as effective means of solving the problem. They are used in situations where breakdown in communication is more likely to take place. According to Carl Rogers, this strategy is called “empathic listening†(Rogers 284). In this kind of situation, arguers refrain from passing judgment on the audience’s ideas until they have listened attentively to the audience’s perspective. Instead of creating a situation where the audience feels offended and attacked, arguers show understanding of the opponents’ position. Understanding, as Rogersexplains, means “ to see expressed idea and attitude from the other person’s point of view, to sense how it feels to him, to achieve his frame of reference in regard to the thing he is talking about.â€Â These principles sympathize with the other argument and this, in turn, will lead to mutual respect and understanding. This psychological approach highlights shared knowledge and establishes common ground through which people can negotiate and listen to one another instead of fighting.

Of course there are advantages of the Rogerian strategy, one is bridging the gap between arguer and audience. As Young, Becker, and Pike explain, the Rogerian Argument is based on the assumption that out of a need to maintain the unchanging status and the credibility of their image, individuals may reject ideas that are threatening to them (274). It is only through the elimination of that threat individuals consider a change in perception. Unlike the traditional argument, the Rogerian argument puts more emphasis on the common values people share with one another. The win or lose situation is not really emphasized or even brought to the surface here. Instead of one wining, both arguer and audience win (For more details on this aspect, see Barnet & Bedau 416).

Another advantage of the Rogerian strategy is that arguers examine ways to explore common ground. For example, in an argument in favor of abortion, arguers begin their statement by showing their understanding and respect for those who believe that abortion should be legalized. They may also discuss situations where abortion is the only choice – in cases where the mother is endangered, or cases of incest and rape. In trying to establish common ground, arguers attempt to sympathize with the audience’s position in a rather fair and objective manner so the audience feels that the arguer is dealing with this subject logically and reasonably.

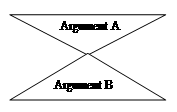

Within the core of the Rogerian argument, arguers state their position objectively, in an attempt to avoid using offensive language and give the audience the impression that their position is better than the audience’s. Instead, they examine situations where their position is valid and explores how they differ from the audience’s. For example, arguers might state that while abortion is understood in certain situations, there are moral, ethical, religious and health problems associated with legalizing abortion. This position is then re-emphasized in the conclusion to make sure the audience realizes that arguer has made some concessions with regard to the audience’s position. In order for the argument to be successful and convincing, arguers have to show the audience how their argument is more beneficial. This idea has not really been addressed in the traditional form of argument where arguers focus on three main components: claim, reasons and evidence. However, in the Rogerian argument the arguer states the opponent’s position, showing the contexts in which it is valid. He then states his own position, showing the contexts in which it is valid. After that, arguers examine the situations to show how the opponent’s position would benefit if they were to adopt their (arguer’s) position.  The goal of arguers is to induce readers to consider their position and to understand it (Young, Becker, and Pike 275). That is, arguers try to make the audience understand their position as mutually related with the larger system of values that is shared by both. They want the audience to feel that they are insiders not outsiders. One approach to this is to state the opponent’s position accurately and completely, and sensitively, trying not to pass any judgment. Obviously, the traditional argument fails either because readers refuse to listen or refuse to admit that they are wrong.  The following diagrams show the differences between the Rogerian argument and the traditional form of argument.

Diagram (2): Traditional Form of Argument |

Diagram (3): Rogerian argument |

As demonstrated above, Diagram (2) represents the traditional form of argument, whereas Diagram (3) represents the Rogerian argument. In the above two diagrams, emphasis should be placed on the shaded area, where the two arguments overlap. It can be seen that in Diagram (2), there is no overlapping between the two arguments. This means that there are no shared values, grounds, and beliefs. In situations like these, minimal changes often seem unconceivable. However, in Diagram (3), the focus is on the shared values and beliefs.  Arguers’ goal is to get readers to reciprocate, and to establish an area where readers’ argument is valid. Here, maximum changes often seem conceivable. So, one can see that the two strategies represented in Diagrams 2 and 3 are cognitively different. The traditional argument focuses on providing a detailed description of what the arguer’s position is. The argument is analyzed. Then, evidence to support the position is provided. Therefore, the traditional form of argument focuses on how and why. It is a type of textual analysis that allows the arguers to break their argument into different sections, such as claim, evidence, and overall evaluation. The conclusion here would be that we have two arguments and each arguer tries his/her best to convince the other that his/her argument is more valid than the other. There is a possibility the both arguers may never agree with one another, as each one believes in his/her argument. Breakdown in communication is highly possible (Hairston 373).

The Rogerian argument, on the other hand, focuses on what is shared between the arguer and the opponent. All modes of persuasion are used to break down the opponent’s resistance to the argument. By being empathic, using Carl Rogers’ term, the arguer can succeed in changing the opponent’s mind. That is, the Rogerian argument is a non-judgmental argument. It doesn’t really classify whether or not the opponent’s argument is wrong. Arguers don’t put their argument forward until they have carefully restated the opponent’s position, showing their understanding of the other argument and at times examine situations where the opponent’s argument is valid. Adopting this particular strategy conveys to the other the sense that opponents’ position is understood and the two parties are more similar than different, thereby creating a context for successful communication (Hairston 272).

Role of Rhetoric in the Teaching of Writing

Before I show how rhetoric, particularly Rogerian rhetoric, plays an important role in the teaching of writing, a definition of rhetoric must be introduced.   According to Aristotle, rhetoric is the writer’s ability to use all the available means of persuasion (Aristotle 15). Aristotle describes three main forms of rhetoric. These are Ethos (credibility of source), Logos (appeal to logic), and Pathos (appeal to emotions). It is to be noted that writers can recognize the effect of the argument by identifying these three forms of rhetoric, but they also have to understand that the language and style of the argument has a tremendous impact on the reader. Here is an example that shows how a rhetorical aspect is being used to address the reader:

Let us begin with a simple proposition: What democracy requires is public debate, not information. Of course it needs information too, but the kind of information it needs can be generated only by vigorous popular debate. We do not know what we need to know until we ask the right question, and we can identify the right questions only by subjecting our own ideas about the world to the test of public controversy. Information, usually seen as the precondition of debate, is better understood as its by-product. When we get into arguments that focus and fully engage our attention, we become avid seekers of relevant information. Otherwise, we take in information passively-if we take it in at all. (Wood 208)

The above excerpt indicates that the logical style, as the rhetorical aspect, is used to addresses the mind not the feelings of the individual. The arguer attempts to stir peoples’ minds to think cognitively of the argument. As a result, the arguer expects a logical response from his readers.

Establishing credibility is another rhetorical aspect of the argument of which arguers should be aware. Here, arguers attempt to be genuine in their presentation. They focus on realistic views that are of interest to the public. Exaggeration is not at all acceptable in this style. Therefore, understanding the readers’ background and their social values is essential. It is only through these characteristics of an argument arguers can win the trust of the reader.

Within this style, connotative words are an asset to the arguer; they are emotionally loaded words. They are used to evoke feelings about what people regard as good or bad. Arguers use the pathos style to stir the emotion of people about a specific issue.   Here is an example from an essay written by Sara Rimer and published in the New York Times and quoted by Wood:

America has been bombarded with television images of the youth of South-Central Los Angeles: throwing bricks, looting stores, beating up innocent motorists. The Disneyland staff that interviewed the job applicants, ages 17 to 22, found a different neighborhood. (211)

It should be pointed out that arguers should expect that the emotional style creates an emotional response on the part of the reader. Emotionally charged words can affect the conviction of the reader. Words such as looting,beating, throwing bricks, innocent motorists, etc. are emotionally loaded words. The reader is expected to respond to these words emotionally and in turn be convinced that the argument expressed in the essay is valid. At this point, the reader may change his/her mind if he/she had different view from what has been expressed in the essay.

As for the source of credibility (ethos), it should not be taken lightly. A good disposition will do a whole world good. The arguer should to be good, because the reader will not trust the arguer if he thinks him bad. As Aristotle points out that the arguer must be aware of the whole range of human ethos, since he must understand all human motives and emotions and their consequences ((58). Aristotle believes that the arguer should have resources from which he can draw his arguments and substantiation. Using these three forms of rhetoric, whether in classical argument or in the Rogerian argument, or being aware of their effect in writing strategies, is what distinguishes between competent and incompetent writers.

Rogerian Rhetoric for the Writing Student

As the Rogerian argument fosters dialogue and reciprocity, it can be very helpful to our students who feel a sense of threat when using the traditional argument. Students feel at times that their existence is threatened by the kind of disagreement with other people’s perspectives. Also, a large percentage of our students feel intimidated by the classical argument, as it requires them to be confrontational and one-sided. Those students can take advantage of Rogerian argument in terms of its mutual understanding between the two parties concerned. In order for students to feel accepted, they must feel that they are first understood. Along these lines, Rogers points out:

If a person is accepted, fully accepted, and in this acceptance there is no judgment, only compassion and sympathy, the individual is able to come to grips with himself. (305)

Another area that needs to be emphasized, as Bator explains, is the notion of intention. In the traditional form of argument, students feel that they need to attack the other views in order to win the argument (429). This strategy more than likely upsets the students as they feel the need to be friendly and more cooperative. In contrast, the Rogerian strategy gives them some relief. Students feel they are more likely to be accepted and their ideas and views are more likely to be appreciated. This means that the traditional argument emphasizes control over the opponent, whereas the Rogerian argument emphasizes mutual communication. Putting the Rogerian principles into use will eliminate breakdown in communication, and the tendency to be evaluative can be avoided. Such principles provide a solution by creating a situation in which each of the different parties comes to understand the other’s point of view. As Rogers explains, “this situation has been achieved when, in practice, even when feelings run high, by the influence of a person who is willing to understand each point of view empathically, and thus acts as a catalyst to precipitate further understanding†(336). As for mutual communication, Rogers explains:

Mutual communication tends to be pointed toward solving a problem rather than toward attacking a person or group. It leads to a situation in which I see how the problem appears to you, as well as to me, and you see how it appears to me, as well to you. (336)

As for both teachers and students of writing, the Rogerian strategy encourages students to view their writing as their first step to build bridges and winning over open minds rather than being prompted to view the essay only as a finished rhetorical product serving as an ultimate weapon for conversion (Bator 431). Instead, students vary their views on the issue, think of possible ways in which the opponent’s argument is valid, construct unthreatening perspectives on the issue, and try to understand and accept the opponent’s views while uncovering areas in which the truth of both arguments can be approximated.

Conclusion

In rhetorical transactions, the traditional argument does not lend any advice as how to deal with counter-arguments. In situations where people are very strong in their beliefs and values, the traditional argument is in effective. Any logical demonstration in such circumstances seems illogical. Therefore, I believe that the Rogerian strategy works effectively when students encounter controversial issues. Also, defining a concept, exploring a problem, or discussing a situation are all areas where students feel more comfortable writing than attacking an opponent. At least, the Rogerian argument presents our students with an alternative to the traditional argument in which situations are tense between writer and reader. Students should be trained on how to use the Rogerian strategy as it allows them to have more than one acceptable conclusion. Bator rightly explains that many of the issues our students deal with in classrooms are issues that allow the writer or reader to have more than one perspective, taking into account that our students have not yet reached a stage where they have adequate potentials for ethical reasoning. They also haven’t reached a stage where their ethical principles are self-formulated and self-regulated even if those principles conflict with society’s rules.  Bator goes on to say that “the young writer is hard-pressed both to establish a valid stance on the problem presenting itself and at the same time seek to persuade other persons holding antagonistic points of view that he or she is in fact right†(431).

Along these lines, Brent points out that, of course, any argumentative strategy is not excluded from any form of criticism. The Rogerian strategy may be described as non-combatant, non-confrontational, and impractical.  However, these problems may result from the failure to recognize just what the Rogerian rhetoric really is (84-85).  Also, teaching students to put themselves in other peoples’ shoes is not something that is easily obtainable. Therefore, instead of imagining an isolated set of arguments, as in the traditional argument, students emphasize the entire worldview that allows those arguments to exist or make them valid (Young, Becker, and Pike 30). Also, the Rogerian argument may be seen as shrewd or devious. This means that the writer acknowledges unwelcomed views and attempts to show the reader that his ideas are being appreciated by flattering him.

Despite such criticism, I believe that the Rogerian rhetoric has much to offer. It prepares students to have extra skills on the job or in the society. It encourages communication and dialogue. It seeks to gain the audience’s trust. Unlike the traditional argument where language is used to stir peoples’ feelings and emotions in order to control the reader, the Rogerian argument uses language objectively to create situations conducive to cooperation and mutual understanding. Above all, the Rogerian argument is a strategy where students can ultimately build their confidence.

Works Cited

Aristotle. The Art of Rhetoric. Translated by John H. Freese. Massachusetts: Harvard University press, 1976. Â

Brent, D. “Rogerian Rhetoricâ€.  In Argument Revisited. Argument Redefined: Negotiating Meaning in the Composition Classroom. Ed. Barbara Emmel. Paula Research, and Deborah Tenny. Sage, 1996.

Barnet, S. & Bedau, H. Current Issues and Enduring Questions. Sixth Edition. New York: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2002.

Jordan, John. E. Using Rhetoric. New York: Harper & Row Publishers, 1965.

Herrick, James, A.  The History and Theory of Rhetoric. Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 2001.

Bator, P. (1980). “Aristotelian and Rogerian Rhetoricâ€.  College Composition and Communication 31 (1980): 427-432.

Hairston, M. “Carl Roger’s Alternative to Traditional Rhetoricâ€.  College Composition and Communication. 27 (1976): 373-377.

Rottenberg, Annette, T. Elements of Argument. New York: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2000.

Wood, Nancy, V. Perspectives on Argument. Third Edition. New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 2000.

Rogers, Carl, R.  On Becoming a Person: A therapist’s View of Psychotherapy. New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1995.

Young, R. E., A. L. Becker and K. L. Pike.  Rhetoric: Discovery and Change. New York: Harcourt, 1970.